|

From:TheBahamasWeekly.com Bahamas Weather

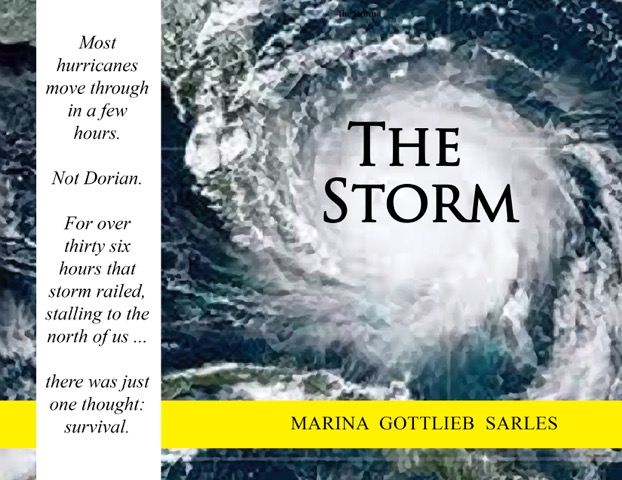

The Storm

Waiting for a hurricane like Dorian—a Category 5 with winds gusting over 200 mph accompanied by a sea surge of some 22 ft—was, in and of itself, an anticipatory trauma. Stress levels erupted as my husband, Jamie and I thought about the future and the losses the storm might bring. Preparations and television reports showing the constant ‘cone of uncertainty’ disrupted our daily life creating high levels of anxiety. Did we have adequate water and food to sustain us? How long would we be without power? Did we have enough gas? What about our shutters and the generator? And running under all this frenzied planning was a constant current of fear of the unknown. How would we survive this physically, financially? How would our community survive? Would it ever bounce back? Would we have to leave if our island became a war zone? Where would we go? There was no way to stop the distressing existential thoughts. Just keep moving. Finally, when the last towels were stacked near the windows and doors and our documents and valuables packed in a waterproof container—the preparations were complete. However, nothing, and I mean nothing could have prepared us for the devastating impact of this particular storm.

When the wind started howling, our television was still working. We hunkered down and in silent horror watched as Dorian ravaged the nearby, neighboring island of Abaco, my childhood home where my brother and his family still lived and where Jamie and I had built our dream cottage—the place we hoped to retire to in years to come. In minutes, right before our eyes, trees, houses, government buildings, cars, planes were reduced to crumpled wreckage—images that began creating hotspots of trauma in my brain. Boats were turned upside and washed ashore. In the streets, the water was rushing through like a mighty tidal wave. I saw a woman running with a child in her arms, screaming to be spared. As long as I live, I will never forget that picture. It is seared in my sight.

A man cried out: “My roof is gone! My neighbor’s house is gone. People are being washed away in front of me. This storm will kill us all. Abaco is finished! Finished! God help us!”

Moments later, we lost the connection to the brave ABC team shooting the footage. Right after that we lost power too— a scary darkness settling over us. The eye of the storm now was headed straight for the eastern part of our island, Grand Bahama. In my heart, I knew that the insubstantial homes in the poorer settlements would never withstand the force of this tempest. How would they survive? I said a prayer. What else could I do in the face of such impending doom? We switched on the radio. Nothing. The wind had already ripped down the tower. I heard my phone ding. What’s App was still working. Someone sent a message. “Terrible flooding in the center of town and in the east of Grand Bahama. Water rushing from the north and the south. In many places its sea to sea. Water 23 feet high. Wind gusting over 200 mph. People terrified of drowning are crawling into attics but the water is at their throats. We think many are already dead. Some are breaking through the roofs trying to save themselves. No rescues possible in this raging wind.”

By now we knew that the worst tropical cyclone ever to strike the Bahamas was hitting us too. We were living a catastrophe. I remember trembling, the rattling noises sounding like death knocking at the door. The wind howled, relentlessly smashing shingles, breaking glass and roaring across our roof like a never-ending freight train. The sound still lives in me. The smell of salt and metal and sulfur come back, too, as I write this making my stomach churn. I tried to lie down. It was late at night. I lit my flashlight hoping to keep my fear at bay but our building shook as if an earthquake had gripped the foundation. Rain began to pour through the ceiling. I got up to fetch a bucket. For hours the gale persisted, whipping at us with unyielding rage. I covered my ears to drown out the sound. But to no avail. Surely the roof would fly off exposing us to death or some kind of injury. At some point, I started yelling back at the gusts. “Stop! For God’s sake stop!” They did not take heed. I was just a frail human whose voice did not carry weight in the face of Nature’s wrath.

Most hurricanes move through in a few hours. Not Dorian. For thirty six hours that storm railed, stalling to the north of us before deciding to move away. In that time, many lives were lost, structures were flattened and swept out to sea. The deluge of sea water continued. People found themselves unable to combat the high levels of stress that rose like the tide through their psyches and physical bodies. Although the storm made landfall in Grand Bahama on Saturday, it was Tuesday before the water receded and survivors could cautiously look around to assess the immeasurable external damage. However, no one could have gaged the terrific build-up of emotional and psychological scarring that had taken place within the heart and soul of the community. For that we would have needed an army of therapists. There was only one thought—survival.

Aftermath Shell-shocked, my husband and I stepped outside our building. How could the sun lend such a brilliant, honeyed light to our battered, gray surroundings, to the trees broken and burned brown by sea water? I felt betrayed—almost as if Nature was mocking us. Nature had always been my source of inspiration, my place of refuge but now I felt as if I could not trust it. It could turn on me at any time. I was angry but I couldn’t rage.

Neighbors gathered, some of them recounting their ordeal, others, like me, were mute and deep inside themselves. “What now?” they queried with hollow faces. They all looked to my husband for answers.

Prior to the storm, Jamie, a dedicated Rotarian joined the team of the Rotary Disaster Relief Efforts organization on Grand Bahama. Fortunately, he is a true first responder who possesses unique qualities for assisting, structuring and bringing things together. Even before the storm, he had organized a huge shipment of supplies through a generous client. The harbor had not even opened when containers arrived. Water, canned goods, bleach, baby food, diapers, hygiene products, towels and tarps were all offloaded at the pier and taken to a warehouse for packaging and distribution.

For me, working in that warehouse was a saving grace. While my hands were busy, my mind was distracted. I didn’t know if my brother and his family in Abaco were even alive but I saw terrible drone images depicting what appeared to be a full-blown war-zone. Our home there was surely gone. Reports indicated that a smell of death permeated the air as more than a thousand people had died, their bodies either swept out to sea or buried beneath the debris. Afraid to imagine the worst, I went about my tasks of sorting and packing. At least, I felt useful. Grateful too, for the deep sense of comradery between those of us who volunteered. Some had lost everything, narrowly escaping with just their lives yet they gave their full support not even taking time to sift through the ruins of their homes to see if any cherished memories might be salvaged. Somehow their losses along with their inner strength helped me remember that I could tap into my own ability to get through the hard times.

As soon as the roads were passable, Jamie and I headed out East with a truckload of goods. On the way, we saw the true scale of Dorian’s destruction, the stark reality of the savage disaster on Grand Bahama. Entire settlements were wiped away. Cars lay in the sea, boats on land. The world was upside down. Homes looked like graveyards of wooden planks. Those that stood were ghostly shells filled with rocks and mud. In the heat, the ever-present, creeping, toxic, earthy smell of mold lingered. Even if the survivors had a corner to live in, they were exposed to the awful effects of this menacing health threat feeding on rotting wood. Alongside the road, glassy-eyed victims were holding their children by the hand. Overhead, I could hear the sound of US army helicopters. It sounded like war, like what children in Syria hear every day.

“We have no food, no water,” a man cried as we slowed down to hand out supplies. We gave what we could, promising that more trucks would follow. Everywhere we went, we heard tales of human tragedy and loss. In the settlement of High Rock a woman told me of her neighbor who had run off in search of her mother during the storm. Before wading through the rising surge she handed over her little, three year old son. “Keep him for me,” she cried. “I’ll be back.” But she never returned. She, her mother and her uncle were swept into the ocean. The little boy was now motherless. What a tragedy to start life this way. How often would he ask for his Mama? And how would these feelings of terror and abandonment be held in his tiny body? Who would hold him when the dreams intruded?

In the village of Mcleans Town I met a bone fisherman carrying debris out of his house. “How are you doing?” I asked. He tried to smile but his eyes were frozen. “My three grandsons and my son are gone, swept away right before my eyes.” He let out a hard sigh. “They won’t be back.” And then he just carried on working. Dorian had written a story for every single person we encountered.After weeks of relief work in Grand Bahama, Jamie and I managed to make our way to Abaco. By this time, I knew my brother was alive but living in Nassau, the total devastation of infrastructure making it impossible to remain on the island. As we drove through my hometown of Marsh Harbour, we could not see a single, familiar landmark. I felt numb. At the bottom of our driveway two men, who had accompanied us, pulled out machetes and chain-saws and began attacking the fallen trees and debris. When the path was clear we climbed the hill. My heart was a storm. What would I find? Fearful, I looked. It was beyond grim. Everything was gone—only the cracked foundation of my beloved home remained. The bitter taste of bile burned my mouth. My knees shook. I felt I was in the aftermath of an apocalypse. I kept looking around, afraid that something terrible was lurking in the bushes. I thought I would cry but my tears were frozen hard somewhere inside me. I was experiencing my own trauma. The loss of my family history, of treasured things that for a lifetime had been reminders of my beloved parents, my grandparents. I felt a shock of guilt too. How dare I cry for this loss when others had lost loved ones and so much more? I still had a roof over my head in Grand Bahama, my son, my husband, my dog. But the nausea wouldn’t stop and finally I vomited out the knots. After wiping my mouth clean I stumbled into an area that had once been the guest bedroom. My sight was blurred but as I looked down I saw three triangular pieces of wood. I recognized them as part of a headboard my grandmother from East Prussia had carved. I stooped to turn them over. My vision cleared. There, boldly engraved were the German words: Gott ist gegenwärtig which means God is always present. I swallowed. Around us everything had fallen apart. The hell which now existed was the greatest persuasion of God’s absence and yet there it was—the Promise, the invitation to stay connected even in the hardest of times. I picked up the fragments. I would frame them and hang them on my wall as an eternal reminder that no matter what, Grace abides. A New Norm Years ago, while at a Center for Intentional Living (CIL) retreat that I attend yearly, a friend of mine despairingly said to our wonderful mentor, Dr. Alexis Johnson, “Arghh, my life is just so normal.” Without missing a beat Alexis responded, “Normal is good.” I looked at her in surprise wondering if ‘normal’ was truly the best life lived. Don’t we all want something new and different? Exciting? Well, after the trauma of Dorian, I truly understand what Alexis meant and as every day passes I find myself just trying to adjust to a new norm where unpotable, salty water from the tap is an ordinary occurrence and where my washed hair is always a salty mess. I no longer have a car and my home was blown to smithereens but somehow I have accepted these things. They have taught me to not be attached. However, what’s hard is the fear that another storm could come. Another Dorian could sweep thousands more into the sea. What if I end up being the only person left to walk our battered shores? This thought of utter aloneness—as farfetched as it is—fills me with angst and often at night, when the rain starts and the wind picks up, I find myself pacing the hallway. I know its PTSD. In the supermarket, I hear children asking their mothers, “Mama, what if it happens again?” They are scared too. I worry for them, for the trauma that sits in their young hearts.

Learning to live with the fear of another storm is the new norm now. Global warming is the new norm, the catastrophic element we face every day on our low lying islands. How do we hold this fear without losing trust? We are all trying to find our place in this new state of being. And yet, in an environment that appears broken I sense a change in people. Despite the high level of exposure to human suffering and cruel losses, we seem to carry on with more kindness, more compassion for one another as if the collective trauma has brought us all closer. We talk to strangers all the time now. Perhaps disasters do that.

|